Goal:

Maintain and modernize the transportation system and plan for its resiliency.

Objectives:

The Boston region’s transportation infrastructure is aging and the demands on roadway and transit facilities have stressed the infrastructure to the point that routine maintenance is insufficient to keep up with necessary repairs. As a result, there is a significant backlog of projects required to maintain the transportation system and assets in a state of good repair, including projects that address bridges, roadway pavement, transit rolling stock and infrastructure, and traffic and transit control equipment. In addition, parts of the transportation system may be compromised if climate change trends continue as projected.

System preservation is a priority for the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) because the region’s transportation infrastructure is aging. The demands placed on highway and transit facilities have stressed the system to the point that routine maintenance is insufficient to keep up with the need. As a result, there is a significant backlog of maintenance and work to maintain the system in a state of good repair on the highway and transit systems, including on bridges, roadway pavement, transit rolling stock, and other infrastructure. It is also important to improve the resiliency of the region’s transportation system to prepare for existing or future extreme conditions, such as sea level rise and flooding. In addition, the movement of freight is critical to the region’s economy, so it is important to protect all freight network elements, including port facilities that are vulnerable to climate change impacts.

To support preservation of the transportation system, the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) requires states, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), and public transit providers to implement a performance-based approach to making investments to bring and keep transportation infrastructure in a state of good repair. This approach includes developing asset management plans, setting performance targets, and monitoring preservation outcomes for these assets, which include pavement, highway and transit bridges, and transit infrastructure and rolling stock.

The transportation system must be brought into a state of good repair, maintained at that level, and enhanced to ensure mobility, efficient movement of goods, and protection from potential sea level rise and storm-induced flooding. Financial constraints require the Boston Region MPO, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), and the region’s transit agencies to set priorities, considering the most crucial maintenance needs and the most effective ways to program their funding. At the same time, infrastructure that could be affected by climate change must be made more resilient.

The MPO’s understanding of system preservation and modernization needs are informed by various planning processes conducted by transportation agencies in the region. MassDOT has developed a Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP), a risk-based asset management plan for bridge and pavement assets on the National Highway System (NHS) in Massachusetts, which will help MassDOT plan to improve NHS asset condition and performance.1 Similarly, the transit agencies in the Boston region—the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA), and the Cape Ann Transportation Authority (CATA)—have produced Transit Asset Management (TAM) plans, which will help them prioritize investments to maintain state of good repair in transit vehicles, facilities, and other infrastructure. These agencies, along with the MPO, monitor changes in asset condition over time using federal established performance measures for NHS bridges, pavement, and transit assets.

The MBTA’s Strategic Plan and 25-year investment plan, Focus40, complement the asset management plans by specifying state of good repair and modernization programs and projects, both for individual MBTA services and the system as a whole. Likewise, MassDOT’s annual Capital Investment Plan (CIP) development process places top priority on investments that support transportation state of good repair and reliability. In addition, the report recently released by the Commission on the Future of Transportation in the Commonwealth, Choices for Stewardship: Recommendations to Meet the Transportation Future, includes recommendations to modernize existing state and municipal transit and transportation assets to more effectively and sustainably move more people throughout the Commonwealth and make transportation infrastructure resilient to a changing climate. MassDOT and the MBTA track performance over time both through annual reporting conducted by the Commonwealth’s Performance and Asset Management Advisory Council and through MassDOT’s Tracker.

To address identified needs, the MPO can invest its discretionary funds also known as Regional Target dollars to and coordinate with its partners to support transportation infrastructure preservation and modernization. The MPO can use information from the aforementioned planning processes to consider and provide feedback on projects and programs that agencies bring forward for inclusion in the MPO’s Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) and Transportation Improvement Program (TIP). The MPO may also choose to support some of these or other system preservation investments directly with its Regional Target funds. When spending its Regional Target funds, the MPO uses current system preservation-related TIP evaluation criteria to determine whether a project improves substandard pavement, bridges, sidewalks, signals or transit assets, or otherwise improves emergency response or the transportation system’s ability to respond to extreme conditions. The MPO may be able to use information from MassDOT and transit agency planning processes to supplement its existing project evaluation process.

Table 5-1 summarizes key findings regarding system preservation and modernization needs that MPO staff identified through data analysis and public input. It also includes staff recommendations for addressing each need. Chapter 10 provides more detail on each of the recommendations. The MPO board should consider these findings when prioritizing programs and projects to receive funding in the LRTP and TIP, and when selecting studies and activities for inclusion in the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP).

Table 5-1

System Preservation and Modernization Needs in the Boston Region Identified through Data Analysis and Public Outreach and Recommendations to Address Needs

| Emphasis Area |

Issue |

Needs |

Recommendations to Address Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

Bridges |

Bridge condition: Currently, of the 2,811 bridges in the region 151 (five percent) are structurally deficient. Approximately 12 percent of the National Highway System (NHS) bridges in the Boston region are considered to be in poor condition. |

Meet MassDOT’s performance measure to prevent the number of structurally deficient bridges from exceeding 300 statewide.

Maximize the number of bridges in the region considered to be in good condition, and minimize the number of bridges considered to be on poor condition. |

Existing Programs Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

|

Bridges |

Bridge Health Index scores: Currently, as measured on this index, 33 percent of bridges in the region are in good condition, 35 percent are in poor condition, and 32 percent have not been rated because of missing data. |

Meet MassDOT’s performance measure to maintain a systemwide Bridge Health Index score of 92 (measured on a scale of zero to 100) in calendar year 2020 and a score of 95 in the long-term. |

Existing Programs Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

|

Pavement Management |

Condition of MassDOT-maintained roadways: Of the roadways in the region maintained by MassDOT, 69 percent are in good condition, 25 percent are in fair condition, and six percent are in poor condition. |

Monitor the MassDOT Pavement Management program. MassDOT-maintained arterial roadways make up 55 percent of monitored roadways, however 86 percent of the arterial roadways are in poor condition; lengthy arterials in poor condition are located in Arlington, Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Lynn, Malden, Medford, Newton, and Salem. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvement Program Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

|

Pedestrian Facilities |

Sidewalk location and condition: Of the sidewalks in the state, 81 percent are municipally owned. Neither the MPO nor MassDOT maintain pedestrian facility data. Knowing where sidewalks are located or absent, and their condition, is a key element in planning. |

Identify the location of sidewalks and their condition; identify those around transit stations. |

Existing Programs Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections Program Study issues through the Bicycle and Pedestrian Support Activities program (UPWP) Existing Studies Addressing Priority Corridors from the LRTP Needs Assessment (FFY 2019 UPWP) Addressing Safety, Mobility, and Access on Subregional Priority Roadways (FFY 2019 UPWP) Proposed Study Regionwide Sidewalk Inventory |

Transit Asset State of Good Repair |

State of good repair for the transit system: The region’s transit systems include vehicles, facilities, and fixed guideway that do not meet state of good repair thresholds defined by the federal government. Other transit assets, such as track signals and power systems, need maintenance and upgrades to support safe, reliable service. |

Identify and invest in priority transit state of good repair projects, as identified in Focus 40, TAM plans, and other prioritization processes. |

Proposed Program Transit Modernization Program

|

Transit Asset Modernization |

Obsolete infrastructure: Even if in a state of good repair, obsolete infrastructure inhibits transit systems’ abilities to adapt to change and serve customers. Examples of necessary upgrades include increasing the resiliency of transit system power supplies, incorporating modern doors and platforms into subway services, and making transit stations—such as Oak Grove Station and Natick Center Commuter Rail Station—fully accessible to people with disabilities. |

Support investments that improve the accessibility of transit stations, bus stops, and paratransit services, such as those identified through the MBTA’s Plan for Accessible Transit Infrastructure (PATI) process. Support investments that upgrade transit fleets, facilities, and systems to provide more efficient, reliable, and sustainable service. Support climate vulnerability assessments and invest in projects and programs resulting from these processes. |

Existing Programs Bicycle Network and Pedestrian Connections Program Study issues through the Bicycle and Pedestrian Support Activities program (UPWP) Support MassDOT’s Climate Adaption Vulnerability Assessment and invest in recommended projects Proposed Program Transit Modernization Program Proposed Study Research climate change resiliency options for transportation infrastructure |

Freight Network |

Many express highways are built to outdated design standards for trucks. Roads connecting to major freight facilities and routes need to support trucks as well as other types of vehicles. |

Maintain and modernize the roadway network. Improve connections between intermodal facilities and the regional road network. Maintain truck access on roadways designed to Complete Streets standards. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvement Program Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Research strategies to improve bottleneck locations through the Bottleneck Program Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program |

Climate Change Adaptation |

Some transportation facilities and infrastructure, including tunnels, are located in places vulnerable to flooding and other hazards. |

Retrofit or adapt infrastructure, including the Central Artery, to protect it from the impacts of hazards and climate change. |

Existing Programs Intersection Improvement Program Complete Streets Program Major Infrastructure Program Support to MassDOT’s Climate Adaption Vulnerability Assessment Proposed Program Interchange Modernization Program

Proposed Study Research climate change resiliency options for transportation infrastructure

Other Actions Coordinate with municipalities and state and regional agencies on ways that the MPO can support resiliency planning Emphasize TIP resiliency and adaptation criteria |

UPWP = Unified Planning Work Program.

Source: Boston Region MPO.

This section presents the research and analysis MPO staff conducted to understand transportation system preservation and modernization needs in the Boston region, which have been summarized in the previous section. Supporting information that MPO staff used to understand preservation and modernization needs is included in the appendices of this Needs Assessment:

This section also includes a summary of input staff gathered from stakeholders and the public about transportation system preservation and modernization needs and proposed solutions to meet those needs. Staff considered this input when developing recommendations to achieve the MPO’s system preservation and modernization goals and objectives.

This section focuses on the condition of the region’s roadway network, which includes pavement, bridges, and pedestrian facilities.

According to MassDOT’s 2017 Year-End Roadway Inventory Report, the Boston region includes 1,154 lane miles of interstate highways, 5,252 lane miles of arterial roadways, 2,414 lane miles of collector roadways, and 14,162 lane miles of local roads.2 MassDOT regularly monitors the region’s interstate highways and a portion of the region’s arterial and collector roadways to assess pavement condition. MassDOT’s pavement management program assigns roadway segments a pavement condition value based on the International Roughness Index (IRI), which evaluates pavement roughness using a mathematical method.3

The Boston Region MPO currently does not maintain an independent pavement management tool, but relies on MassDOT’s pavement management program to understand the condition of interstate, arterial, and access-controlled arterial roadways in the Boston region. MPO staff used geographic information system (GIS) software to join 2017 data from MassDOT’s pavement management system and roadway characteristics from the 2017 Roadway Inventory file to estimate the current condition of monitored roadways in the region. MPO staff was able to estimate pavement data for nearly 100 percent of interstate lane miles in the region, 96 percent of access-controlled arterials and collector lane miles in the region, and 33 percent of non-access controlled arterial and collector lane miles in the region. MPO staff categorized IRI values for segments on this network as good, fair, or poor using the classification scheme in its TIP evaluation criteria.4

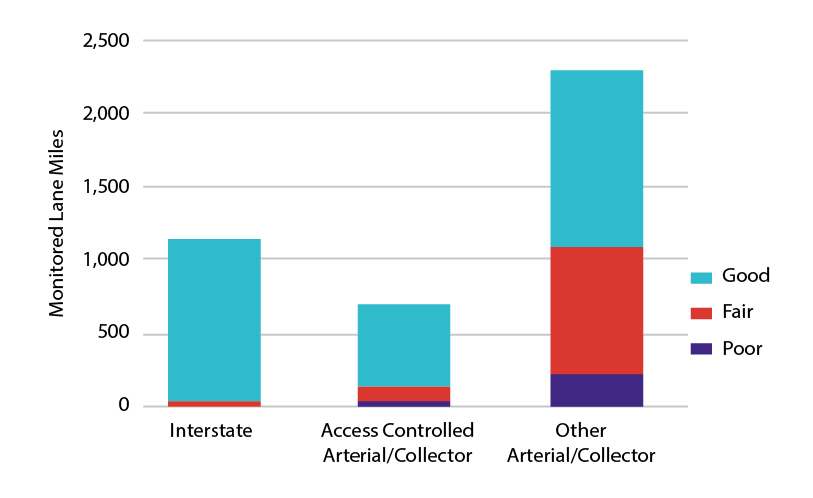

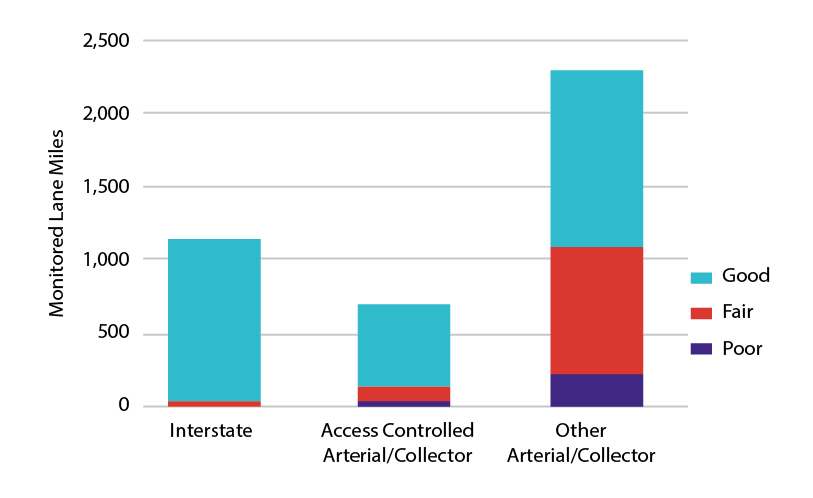

Figure 5-1 shows the number of lane miles of monitored roadways, by roadway type, that are in good, fair, or poor condition.5 Approximately 69 percent of all monitored roadway lane miles are in good condition, 25 percent are in fair condition, and six percent are in poor condition. However, MassDOT-monitored arterial and collector roadways without access controls account for a disproportionate share of monitored lane miles that are considered substandard, or in fairor poor condition. This roadway type accounted for 55 percent of the total monitored roadway lane miles in 2017, but about 86 percent of those lane miles that are in substandard condition.

Figure 5-1

Pavement Condition by Roadway Classification

Note: MPO staff selected pavement data collected during the last five years for analysis. While most of the data presented in this chart was collected in 2017, data for some roadways was collected in 2013, 2015, and 2016.

Source: Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s Pavement Management System, 2017 data set.

The most recent pavement data indicates that the majority of these arterial roadways are located in urban centers. MPO staff analysis of pavement condition in the region shows larger expanses of arterial roadways with poor pavement condition in the urban centers of Arlington, Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Lynn, Malden, Medford, Newton, and Salem. Many of these urban centers are the same ones that MPO staff identified as having poor pavement condition in the last Needs Assessment. Since that time, pavement conditions on more roadways in Arlington, Brookline, and Salem have deteriorated. However, pavement conditions in Everett, Revere, and Somerville have improved.

The USDOT performance management framework requires states and MPOs to monitor and set targets for the condition of pavement on NHS roadways, a network that includes the Interstate Highway System and other roadways of importance to the nation’s economy, defense, and mobility. Massachusetts has 3,204 lane miles of interstate roadways, 1,154 lane miles (or 36 percent) of which are in the Boston region. The state’s non-interstate NHS network is made up of 7,319 lane-miles of roadways, and the Boston region contains 2,559 (or 35 percent) of those lane miles. Applicable federal performance measures include the following:

The interstate performance measures classify interstate pavements as in good, fair, or poor condition based on their IRI value and one or more pavement distress metrics (cracking and/or rutting and faulting) depending on the pavement type (asphalt, jointed concrete, or continuous concrete). The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) sets thresholds for each metric that determine whether the metric value is good, fair, or poor, along with thresholds that determine whether the pavement segment as a whole is considered to be in good, fair, or poor condition.6 Non-interstate NHS pavements are subject to the same thresholds for IRI values. States will be required to collect data for the complementary distress metrics starting in 2020, and those data will be incorporated into future performance monitoring.

MassDOT uses information from its Pavement Management program to track the condition of Massachusetts’ NHS network. In 2018, MassDOT established performance targets for these NHS pavement condition performance measures, which are shown along with baseline data in Table 5-2. As with the NHS bridge condition performance targets, the two-year target reflects conditions as of the end of calendar year (CY) 2019, and the four-year target reflects conditions as of the end of CY 2021. While MassDOT has collected IRI data in past years, these federally required performance measures also require other types of distress data that have not previously been required as part of pavement monitoring programs. Setting targets for these pavement condition measures has been challenging given the lack of complete historic data. MassDOT’s approach has been to use past pavement indicators to identify trends and to set conservative targets. MassDOT will revisit its four-year target in in 2020 when more data is available.

Table 5-2

Massachusetts NHS Pavement Condition Baselines and MassDOT NHS Pavement Condition Performance Targets

Federally Required Pavement Condition Performance Measure |

2017 Measure Value (Baseline) |

Two-Year Target |

Four-Year Target |

Percent of Interstate Highway System pavements that are in good conditiona |

74.2% |

70.0% |

70.0% |

Percent of Interstate Highway System pavements that are in poor conditiona |

0.1% |

4.0% |

4.0% |

Percent of non-interstate NHS pavements that are in good condition |

32.9% |

30.0% |

30.0% |

Percent of non-interstate NHS pavements that are in poor condition |

31.4% |

30.0% |

30.0% |

a For the first federal performance monitoring period (2018–21), the Federal Highway Administration has only required states to report four-year targets for pavement condition on the Interstate Highway System. MassDOT has developed both two-year and four-year targets for internal consistency.

CY = calendar year. NHS = National Highway System.

Source: MassDOT.

MPOs are required to set four-year interstate pavement condition and non-interstate NHS pavement condition performance targets by either supporting state targets or setting separate quantitative targets for the region. The Boston Region MPO elected to support MassDOT’s four-year targets for these NHS pavement condition measures in November 2018. The MPO will work with MassDOT to meet these targets through its Regional Target investments.

MassDOT and the MBTA prioritize resources for bridge preservation, as well as repair and replacement, and fund this work through the Statewide Bridge Program and MBTA bridge initiatives. MassDOT and the MBTA maintain a bridge management software tool (PONTIS) for recording, organizing, and analyzing bridge inventory and inspection data. PONTIS is used to guide the Statewide Bridge Program, which prioritizes resources for bridge preservation, repair, and replacement.

As of calendar year 2017, there were 2,811 bridges located within the Boston region. Some are in substandard condition because they have been deemed by MassDOT bridge inspectors to be structurally deficient or weight restricted (posted). Structurally deficient bridges are those that are not necessarily unsafe, but that have deteriorated in ways that reduce the load-carrying capacity of the bridge. A bridge may be posted as weight restricted to ensure traveler safety. Of the 2,811 bridges located in the Boston Region MPO, 151 (five percent) are considered structurally deficient and 102 (four percent) are posted as weight restricted.

The Bridge Health Index (BHI) is an important tool for monitoring bridge conditions. This index provides a comprehensive overview of the condition of all bridge elements across the network. This measure, reported on a scale of zero to 100, reflects inspection data in relation to the asset value of a bridge or network of bridges. A value of zero indicates that all of a bridge’s elements are in the worst condition. A value of 85 or more indicates that the condition of a bridge is good. One-third of bridges in the Boston region (931 bridges) have health indices with a score 85 or greater; 35 percent (972 bridges) have health indices of less than 85; and 32 percent (864 bridges) do not have core element data needed to calculate this value. An additional 44 bridges have health indices of zero. These include railroad bridges, pedestrian bridges, and closed bridges.

The Commonwealth instituted the Accelerated Bridge Program in 2008 to reduce the number of structurally deficient bridges in Massachusetts by funding bridge replacement, rehabilitation, and preservation projects. The program’s goal was to reduce this backlog to below 450 structurally deficient bridges by September 30, 2016. As of that date, the program exceeded its goal, reducing the number of structurally deficient bridges to 432, a 20 percent decline from the initial total of 543 structurally deficient bridges. As of September 1, 2018, the Accelerated Bridge Program had completed 191 bridge projects, 53 of which were in municipalities in the Boston region. Seven bridge projects are still under construction, including four in the Boston region:

Over the course of the Accelerated Bridge Program, over 270 bridges will have been rehabilitated or replaced throughout Massachusetts, and many more will have been improved to address safety needs or support preservation. MassDOT will continue to address structurally deficient bridge projects and other bridge needs outside of the Accelerated Bridge Program.

As of 2018, Massachusetts contains approximately 5,218 bridge structures that are included in the National Bridge Inventory (NBI), and 1,613 (31 percent) of them are located within the Boston region. NBI bridge structures are those that serve vehicular traffic and are more than 20 feet in length.7 More than half of the bridges in the Boston region meet the NBI criteria. As of 2018, the Boston region included 151 NBI bridge structures deemed structurally deficient (about nine percent of all NBI bridge structures in the Boston region). Eighty-two NBI bridge structures were posted as weight restricted (about five percent of all bridge structures in the Boston region). By comparison, Massachusetts had 470 NBI bridge structures deemed structurally deficient and 438 bridge structures posted as weight restricted (nine and eight percent of the state’s bridge structures, respectively).8

To meet federal performance monitoring requirements, states and MPOs must track and set performance targets for the condition of bridges on the NHS. FHWA’s bridge condition performance measures include the following:

These performance measures classify NHS bridge condition as good, fair, or poor based on the condition ratings of three bridge components: the deck, the superstructure, and the substructure.9 The lowest rating of the three components determines the overall bridge condition.10 The measures express the share of NHS bridges in a certain condition by deck area, divided by the total deck area of NHS bridges in the applicable geographic area (state or MPO).

Table 5-3 shows performance baselines for the condition of bridges on the NHS in Massachusetts and the Boston region. As of 2017, MassDOT had analyzed the 2,246 bridges on the NHS in Massachusetts to understand their current condition with respect to the federal bridge condition performance measures. In 2018, the Boston Region MPO performed a similar analysis on the 859 bridges on the NHS in the Boston region. According to these baseline values, the Boston region has a larger share of NHS bridge deck area considered to be in good condition, and a slightly smaller share of NHS bridge deck area considered to be in poor condition, compared to Massachusetts overall.

Table 5-3

Massachusetts and Boston Region NHS Bridge Condition Baselines

Geographic Area |

Total NHS Bridges |

Total NHS Bridge Deck Area (square feet) |

Percent of NHS Bridges in Good Condition |

Percent of NHS Bridges in Poor Condition |

Massachusettsa |

2,246 |

29,457,351 |

15.2% |

12.4% |

Boston Regionb |

859 |

14,131,094 |

19.2% |

11.8% |

a Massachusetts baseline data is based on a MassDOT analysis conducted in 2018.

b Boston region comparison data is based on a Boston Region MPO analysis conducted in 2018.

NHS = National Highway System.

Sources: MassDOT and Boston Region MPO.

USDOT has established 10 percent as a threshold for statewide NHS bridge deck area that is in poor condition, and departments of transportation for states that exceed that threshold must direct a defined minimum amount of National Highway Performance Program (NHPP) funding toward improving NHS bridges. Because more than 10 percent of Massachusetts NHS bridge deck area is in poor condition, MassDOT programs this minimum amount.

States must set performance targets for these NHS bridge performance measures at two-year and four-year intervals. Table 5-4 shows MassDOT’s NHS bridge performance targets, which it established in 2018. The two-year target reflects conditions as of the end of CY 2019, and the four-year target reflects conditions as of the end of CY 2021. These targets reflect anticipated conditions based on historic trends and planned bridge investments. As shown in the table, MassDOT expects there will be a small increase in the share of NHS bridge deck area in good condition by the end of CY 2021, while it expects that the share of NHS bridge deck area in poor condition in CY 2021 will be slightly lower than the baseline.

Table 5-4

MassDOT’s NHS Bridge Condition Targets

Federally Required Bridge Condition Performance Measure |

2018 Measure Value (Baseline) |

Two-Year Target |

Four-Year Target |

Percent of NHS Bridges [by deck area] that are in good condition |

15.2% |

15.0% |

16.0% |

Percent of NHS Bridges [by deck area] that are in poor condition |

12.4% |

13.0% |

12.0% |

CY = calendar year. NHS = National Highway System.

Source: MassDOT.

MPOs are required to set four-year bridge performance targets by either electing to support state targets or setting separate quantitative targets for the MPO area. The Boston Region MPO elected to support MassDOT’s four-year targets for these measures in November 2018. The MPO will work with MassDOT to meet these targets through its Regional Target investments.

An inventory of the location and condition of the region’s sidewalks and walkways is limited, therefore this inventory must be supplemented through ongoing data collection and analysis. Currently, sidewalk inventory data is stored within the Massachusetts Road Inventory File, which is maintained by the MassDOT Office of Transportation Planning (OTP), however data about sidewalk condition is not included.

According to data gathered for MassDOT’s Massachusetts Pedestrian Plan, 81 percent of sidewalks in the state are municipally owned, and MassDOT does not maintain data for these pedestrian facilities.11 Knowing where sidewalks are located or absent, and their condition, is a key element in planning. Collection of these data could contribute to numerous other planning efforts, such as MAPC’s Access Score application, MassDOT’s Safe Routes to School program, and MPO Safe Routes to Transit initiatives.12 A model for such an effort is the sidewalk inventory recently completed by the Capital District Transportation Committee, the MPO serving the Capital District of New York State.13

In addition, MassDOT has implemented a program to reconstruct substandard curb ramps on state-owned roads to meet the obligation of the development of its ADA Transition Plan. In 2012, MassDOT inventoried all 26,000 curb ramps throughout the Commonwealth; almost 6,700 were found to be failing or missing. As of 2017, the number of failed or missing curb ramps had been reduced to 5,200. Additional projects are scheduled for advertisement through 2021.14

Public outreach and data collection from other planning efforts, such as Go Boston 2030, the City of Boston’s transportation plan, identified the need to maintain and upgrade sidewalks throughout the city and especially in and around transit stations.

MassDOT identifies system preservation and modernization needs using an array of asset management systems and planning efforts, including the development process for its Transportation Asset Management Plan for NHS bridge and pavement assets. These processes inform how MassDOT develops it’s rolling five-year Capital Investment Plan (CIP). This plan is focused on three major priorities: system reliability, modernization, and expansion, with reliability being the top priority. For each priority area, MassDOT has established investment programs, which fund relevant capital improvement projects. The Reliability and Modernization Programs relate most directly to the MPO’s system preservation and modernization goal.

The Boston Region MPO TIP reflects federally funded investments MassDOT makes through these programs that affect the Boston region, along with investments that the MPO makes with its Regional Target funds. MassDOT’s and the MPO’s project selection processes complement one another to the extent possible to ensure transportation system preservation and improvement needs are met. Traditionally, MassDOT’s reliability and modernization investments have addressed the vast majority of bridge and NHS pavement maintenance needs in the Boston region, along with other roadway and intersection improvement needs.

The MPO has focused its investments on intersection improvements and roadway reconstruction activities that support Complete Streets or address bottlenecks. The MPO follows a policy of not funding projects that are only for resurfacing pavement and typically does not fund bridge projects, although the MPO does address bridge pavement condition needs through Complete Streets or bottleneck improvement projects. The MPO’s project evaluation process awards points if a proposed project will improve substandard bridges, pavement, sidewalks, or traffic signals. The MPO can use its performance-based planning and programming (PBPP) process to monitor bridge and pavement condition—and potentially the condition of other assets. Finally, the MPO can fund studies and data collection initiatives through its Unified Planning Work Program to inform its understanding of system preservation needs and opportunities to address these needs.

The Chapter 90 Program (named for Chapter 90 of the Massachusetts General Laws), which is administered by MassDOT, also contributes to the Commonwealth’s strategy of preserving existing transportation facilities. This program supports construction and maintenance of local roadways, which are owned and maintained by the cities and towns of the Commonwealth. Typically, the majority of Chapter 90 allocations are allocated for road resurfacing and reconstruction.

As with the roadway network, it is crucial to achieve and maintain the Boston region’s transit systems in a state of good repair to ensure that transit service is safe and reliable. The region’s largest transit provider is the MBTA, which maintains an extensive portfolio of transit assets. These assets are documented in the MBTA’s Transit Asset Management (TAM) plan and related documents and in MassDOT’s Performance and Asset Management Advisory Council 2018 annual report:15

Other MBTA assets include its communication systems and automated fare collection system, the latter of which is made up of more than 3,000 assets, including fareboxes, vending machines, and fare gates.

The Cape Ann Transportation Authority (CATA) and the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA) also own and maintain assets to provide service in the Boston region. As of June 2019, CATA and MWRTA expect to have approximately 33 and 102 revenue service vehicles, respectively, and each agency also owns and maintains several equipment vehicles. Each agency also owns and maintains an administrative facility. As with the MBTA, these agencies strive to maintain their assets in a state of good repair.

The MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA regularly receive funds from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to provide service. These agencies are responsible for meeting planning and performance-monitoring requirements under FTA’s TAM rule, which focuses on achieving and maintaining a state of good repair for the nation’s transit systems. Each year, they must submit progress reports and updated performance targets for TAM performance measures. Transit agencies develop these performance targets based on their most recent asset inventories and condition assessments, along with the capital investment and procurement expectations that are informed by their TAM plans. MBTA, MWRTA, and CATA share their asset inventory and condition data and their performance targets with the Boston Region MPO so that the MPO can monitor and set TAM targets for the Boston region.

The TAM rule specifies four performance measures, which apply to four asset categories: rolling stock (vehicles that provide passenger service), equipment (nonrevenue service vehicles), facilities, and infrastructure (rail fixed guideway systems). Table 5-5 describes these measures.

Table 5-5

Transit Asset Management Performance Measures by Asset Category

Asset Category |

Relevant Assets |

Measure |

Measure Type |

Desired Direction |

Rolling Stock |

Buses, vans, and sedans; light and heavy rail cars; commuter rail cars and locomotives; ferry boats |

Percentage of revenue vehicles that have met or exceeded their ULB |

Age-based |

Minimize percentage |

Equipment |

Service support, maintenance, and other nonrevenue vehicles |

Percentage of vehicles that have met or exceeded their ULB |

Age-based |

Minimize percentage |

Facilities |

Passenger stations, parking facilities, administration and maintenance facilities |

Percentage of assets with condition rating lower than 3.0 on FTA TERM Scale |

Condition-based |

Minimize percentage |

Infrastructure |

Rail fixed guideway systems |

Percentage of track segments with performance (speed) restrictions, by mode |

Performance-based |

Minimize percentage |

FTA = Federal Transit Administration. TAM = Transit Asset Management. TERM = Transit Economic Requirements Model. ULB = Useful Life Benchmark.

Sources: FTA and the Boston Region MPO.

Transit agencies may supplement these federally required performance measures with other measures and indicators to monitor and address the condition of their assets.

The following subsections discuss the MPO’s current performance targets (adopted in March 2019) for each of the TAM performance measures. These performance targets reflect MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA state fiscal year (SFY) 2019 TAM performance targets (for July 2018 through June 2019). MPO staff has aggregated some information for asset subgroups. The tables in this section highlight whether transit agencies expect to see performance for specific asset subgroups get better or worse compared to the SFY 2018 baseline (June 30, 2018).

FTA’s TAM performance measure for the state of good repair for rolling stock and equipment vehicles (service support, maintenance, and other nonrevenue vehicles) is the percent of vehicles that meet or exceed their useful life benchmark (ULB). This performance measure uses vehicle age as a proxy for state of good repair (which may not necessarily reflect condition or performance), with the goal being to bring this value as close to zero as possible. FTA defines ULB as “the expected lifecycle of a capital asset for a particular transit provider’s operating environment, or the acceptable period of use in service for a particular transit provider’s operating environment.” For example, FTA’s default ULB value for a bus is 14 years. When setting targets, each agency has discretion to use FTA-identified default ULBs for vehicles or to adjust ULBs with approval from FTA. The MBTA has used FTA default ULBs for its rolling stock targets; however the MBTA defined its own ULBs, which are based on agency-specific usage and experience, for its equipment targets. CATA and MWRTA have selected ULBs from other sources.16

Table 5-6 describes SFY 2018 baselines and the MPO’s SFY 2019 targets for rolling stock, which refers to vehicles that carry passengers. As shown below, the MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA are improving performance for a number of rolling stock vehicle classes. Transit agencies can make improvements on this measure by expanding their rolling stock fleets or replacing vehicles within those fleets.

Table 5-6

SFY 2018 Measures and SFY 2019 Targets for Transit Rolling Stock

|

|

SFY 2018 Baseline |

SFY 2019 Targets |

|

||

Agency |

Asset Type |

Number of Vehicles |

Percent of Vehicles Meeting or Exceeding ULB |

Number of Vehicles |

Percent of Vehicles Meeting or Exceeding ULB |

Target Compared to Baseline |

MBTA |

Buses |

1,022 |

25% |

1,028 |

25% |

Same |

MBTA |

Light Rail Vehicles |

205 |

46% |

229 |

41% |

Better |

MBTA |

Heavy Rail Vehicles |

432 |

58% |

450 |

56% |

Better |

MBTA |

Commuter Rail Locomotives |

94 |

27% |

104 |

24% |

Better |

MBTA |

Commuter Rail Coaches |

426 |

0% |

429 |

0% |

Same |

MBTA |

Ferry Boats |

4 |

0% |

4 |

0% |

Same |

MBTA |

THE RIDE Paratransit Vehiclesa |

763 |

35% |

763 |

9% |

Better |

CATA |

Buses |

9 |

11% |

8 |

0% |

Better |

CATA |

Cutaway Vehiclesb |

23 |

13% |

23 |

0% |

Better |

CATA |

Trolleys (simulated)c |

2 |

100% |

2 |

100% |

Same |

MWRTA |

Cutaway Vehiclesb,d |

89 |

6% |

93 |

0% |

Better |

MWRTA |

Automobilesd |

9 |

0% |

9 |

0% |

Same |

a The MBTA’s THE RIDE paratransit vehicles data and targets reflect automobiles, vans, and minivans.

b The National Transit Database defines a cutaway vehicle as a vehicle in which a bus body is mounted on a van or light-duty truck chassis, which may be reinforced or extended. CATA uses nine of these vehicles to provide fixed-route services, and 14 of these vehicles to provide demand response service.

c Simulated trolleys, also known as trolley-replica buses, have rubber tires and internal combustion engines, as opposed to steel-wheeled trolley vehicles or rubber-tire trolley buses that draw power from overhead wires.

d MWRTA uses cutaway vehicles to provide fixed route and demand response service, and uses autos to provide demand response service.

CATA = Cape Ann Transportation Authority. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

MWRTA = MetroWest Regional Transit Authority. SFY = State Fiscal Year. ULB = Useful Life Benchmark.

Sources: MBTA, CATA, MWRTA, and the Boston Region MPO.

Table 5-7 shows SFY 2018 baselines and the MPO’s SFY 2019 targets for transit equipment vehicles. MPO staff has aggregated targets for nonrevenue vehicle subtypes for each of the three transit agencies. Similar to transit rolling stock, transit agencies can make improvements on these measures by expanding their fleets or replacing vehicles within those fleets.

Table 5-7

SFY 2018 Measures and SFY 2019 Targets for Transit Equipment Vehicles

|

SFY 2018 Baseline |

SFY 2019 Targets |

|

||

Agency |

Number of Vehicles |

Percent of Vehicles Meeting or Exceeding ULB |

Number of Vehicles |

Percent of Vehicles Meeting or Exceeding ULB |

Target Compared to Baseline |

MBTAa |

1,676 |

20% |

1,676 |

22% |

Worse |

CATA |

4 |

25% |

3 |

0% |

Better |

MWRTA |

12 |

50% |

12 |

50% |

Same |

a MBTA equipment includes both commuter rail and transit system nonrevenue service vehicles.

CATA = Cape Ann Transportation Authority. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

MWRTA = MetroWest Regional Transit Authority. SFY = State Fiscal Year. ULB = Useful Life Benchmark.

Sources: MBTA, CATA, MWRTA, and the Boston Region MPO.

FTA assesses the condition for passenger stations, parking facilities, and administrative and maintenance facilities using the FTA Transit Economic Requirements Model (TERM) scale, which generates a composite score based on assessments of facility components. Facilities with scores below three are considered to be in marginal or poor condition (though this score is not a measure of facility safety or performance). The goal is to bring the share of facilities that meet this criterion to zero. Infrastructure projects focused on individual systems may improve performance gradually, while more extensive facility improvement projects may have a more dramatic effect on a facility’s TERM scale score.

Table 5-8 shows SFY 2018 measures and the MPO’s SFY 2019 targets for MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA facilities. The MBTA measures and targets only reflect those facilities that have undergone a recent on-site condition assessment. The number of facilities that the MBTA has not yet assessed is shown to provide a more comprehensive count of the MBTA’s assets.

Table 5-8

SFY 2018 Measures and SFY 2019 Targets for Transit Facilities

|

|

SFY 2018 Baseline |

SFY 2019 Targets |

|

||

Agency |

Facility Type |

Number of Facilities |

Percent of Facilities in Marginal or Poor Condition |

Number of Facilities |

Percent of Facilities in Marginal or Poor Condition |

Target Compared to Baseline |

MBTA |

Passenger–Assesseda |

96 |

13% |

96 |

11% |

Better |

MBTA |

Passenger– Not Assesseda |

285 |

In progress |

286 |

TBD |

N/A |

MBTA |

Administrative |

156 |

68% |

156 |

63% |

Better |

MBTA |

Maintenance–Assessed |

38 |

In progress |

38 |

TBD |

N/A |

CATA |

Administrative |

1 |

0% |

1 |

0% |

Same |

MWRTA |

Maintenance–Not Assessed |

1 |

0% |

1 |

0% |

Same |

Note: Facilities are classified as being in marginal or poor condition based on FTA’s Transit Economic Requirements Model (TERM) scale. Facilities assigned a rating of less than 3 are considered to be in marginal or poor condition.

a Passenger facilities include stations and parking facilities.

CATA = Cape Ann Transportation Authority. MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

MWRTA = MetroWest Regional Transit Authority. N/A = Not applicable. TBD = To be determined.

Sources: MBTA, CATA, MWRTA, and the Boston Region MPO.

Table 5-9 describes SFY 2018 baselines and SFY 2019 targets for the condition of rail fixed guideways. The MBTA is the only transit agency in the Boston region with this type of asset. The performance measure that applies to these assets is the percentage of track that is subject to performance, or speed, restrictions. The MBTA samples the share of track segments with speed restrictions throughout the year. These performance restrictions reflect the condition of track, signal, and other supporting systems, which the MBTA can improve through maintenance, upgrades, and replacement and renewal projects. Again, the goal is to bring the share of MBTA track systems subject to performance restrictions to zero.

Table 5-9

SFY 2018 Measures and SFY 2019 Targets for MBTA Transit Fixed Guideway Infrastructure

|

|

SFY 2018 Baseline |

SFY 2019 Targets |

|

||

Agency |

Track Type |

Directional Route Miles |

Percent of Miles with Speed Restrictions |

Directional Route Miles |

Percent of Miles with Speed Restrictions |

Target Compared to Baseline |

MBTA |

Transit Fixed Guidewaya |

130.23 |

11% |

130.23 |

10% |

Better |

MBTA |

Commuter Rail Fixed Guideway |

663.84 |

1% |

663.84 |

1% |

Same |

Note: The term “directional route miles” represents the miles managed and maintained by the MBTA with respect to each direction of travel (for example, northbound and southbound), and excludes nonrevenue tracks such as yards, turnarounds, and storage tracks. The baseline and target percentages represent the annual average number of miles meeting this criterion over the 12-month reporting period.

a The MBTA’s Transit Fixed Guideway information reflects light rail and heavy rail fixed guideway networks.

MBTA = Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. SFY = State Fiscal Year.

Sources: MBTA, CATA, MWRTA, and the Boston Region MPO.

Similar to MassDOT’s Highway Division, the MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA identify transit system preservation and modernization needs using asset management systems, by developing their TAM plans, and by monitoring federally required performance measures relating to asset condition. Other processes also inform these agencies’ understanding of these needs. In its 2017 Strategic Plan, the MBTA acknowledged its existing backlog of projects and set a goal to bring all of the MBTA’s assets, including fleets and facilities, to a state of good repair within 15 years; the Strategic Plan also included a spending plan and other action steps to achieve this goal.17 Meanwhile, the MBTA’s Focus40 plan establishes several systemwide programs that address MBTA modernization needs:

Focus40’s mode-specific programs include other planned projects to modernize transit infrastructure and make it more reliable, including initiatives to improve bus fleets and stops, upgrade infrastructure in Silver Line tunnels, upgrade the Green Line’s fleets, infrastructure, and maintenance facilities, and other initiatives.

These various planning processes identify the projects that may be funded through MassDOT’s CIP, which includes investments made by the MBTA as well as the Commonwealth’s regional transit authorities (RTAs), including MWRTA and CATA. Programs that address these agencies’ system preservation and modernization needs also fall into the CIP’s Reliability and Modernization priority areas.

The Boston Region MPO TIP reflects federally funded investments that the MBTA, CATA, and MWRTA make with their federal dollars, along with investments that the MPO makes with its Regional Target funds. While historically the MPO has not flexed its highway Regional Target funds to support transit reliability or modernization projects, it could work with the MBTA and the region’s RTAs to do so through a transit modernization investment program.

The physical condition of the regional roadway network influences the health of the freight transportation system. For freight to move effectively, transportation agencies must consider and make improvements to various components of the network, including roadways, intermodal connection points, interchanges, and truck stops.

Maintaining and modernizing the roadway network directly benefits freight transporters and the customers who receive goods conveyed by trucks. While many express highways were designed in the 1950s, modern highways are designed to higher standards that accommodate the larger-sized trucks of today. One the other hand, the system of arterial roadways that connect regional express highways with local businesses that require freight delivery is undergoing gradual transformation as sections are rebuilt to Complete Streets standards. The emerging practices of arterial roadway design may pose challenges for truck movements if accommodation for modern trucks is not addressed at the outset. The viability of local merchants is key to supporting livable neighborhoods and reversing overdependence on the retail mall concept. However, the ability of “Main Street” merchants to receive deliveries by truck needs to be understood as a requirement for their viability.

When making improvements to the freight network, transportation agencies must recognize the following freight-related concerns:

Intermodal freight connections in the Boston region are almost all between rail and truck or between ship and truck. These intermodal terminals—whether publicly owned, such as the Conley Container Terminal in South Boston, or privately owned, such as the bulk commodity terminals on the Mystic and Chelsea Rivers—finance their terminal investments outside of the MPO’s planning process. However, the MPO may identify opportunities to improve connections between these intermodal terminals and the regional road network. Alternatively, MPO analyses undertaken as part of the UPWP process may identify intermodal freight roadway improvements that could be implemented by others.

The problems of system preservation and capacity management intersect at the issue of obsolete interchanges. The highway interchanges designed in the 1950s are less safe for trucks than modern interchanges, and they lack sufficient capacity to efficiently accommodate today’s traffic. Their ability to accommodate future freight and passenger traffic levels is questionable. Merely reconstructing these interchanges might extend their physical life, but it would extend the use of highway designs unsafe for trucks and inadequate for all traffic. The recently completed Massachusetts Freight Plan recognizes this issue and lists several obsolete interchanges in the MPO region as major freight bottlenecks.

Another freight-related issue is the need for truck rest locations. Rest requirements for truck drivers have become more rigorous in recent years, even as the volume of trucking has increased. There is now national consensus that there is not sufficient parking at useful locations to accommodate trucks during required rest periods. Even if an interstate highway is in excellent physical condition, the system is fundamentally inadequate if truck drivers cannot find suitable rest locations. The MPO staff studied this problem and the findings and recommendations have been incorporated in the Massachusetts Freight Plan.

System preservation needs identified in the Massachusetts Freight Plan can be addressed by the Reliability and Modernization Programs included in MassDOT’s CIP, as discussed previously in the Roadway Network Assets section. The MPO also seeks opportunities to fund freight-supporting projects through its investment programs. The project selection criteria in the MPO’s TIP includes a criterion that examines whether a proposed project will protect freight network elements. Criteria that support other MPO goal areas examine whether proposed projects will improve truck movement and access.

When seeking to maintain the region’s transportation system, the Boston Region MPO will not only have to consider existing challenges related to maintaining a state of good repair and existing environmental risk factors, but also threats posed by a changing climate. There are two aspects of climate change planning—mitigation and adaption. Climate change mitigation generally involves reducing human-caused (anthropogenic) emissions of greenhouse gases. Mitigation is addressed under the Clean Air/Sustainable Communities goal area. Adaptation is a response that reduces the vulnerability of the transportation system to a relatively sudden change and thus offsets the effects of climate change. This System Preservation goal area addresses adaptation.

The effects of climate change include increased days of extreme temperatures (causing asphalt deterioration, and the buckling of pavements and rail lines), sea level rise (causing inundation of transportation systems along the coastline and more severe flooding from storm surges), extreme precipitation (overwhelming storm water drainage systems that may also be compromised by sea level rise and river flooding), and more intense storms (such as Nor’easters that bring snow, flooding, and storm surges).

Transportation infrastructure that is susceptible to climate change and extreme weather includes roadways, bridges, tunnels, subways, commuter and freight rail, ferries, bus facilities, airports, and ports. Much of the key infrastructure in the Boston region is located along coasts and near major rivers and was sited and designed based on historic weather, sea level, and flooding patterns. Adaptation to climate change can take the form of large-scale improvements—such as building infrastructure to protect against sea level rise and more intense and frequent extreme storm events, or improving the quality of road surfaces to withstand hotter temperatures.

Given the MBTA’s central role in the region’s transportation system, increased vulnerability to its infrastructure warrants particular attention. Climate change impacts can also present a number of planning challenges for the freight industry, which in the Boston region relies heavily on the functioning of the surface roadway system. (Hazardous cargo is prohibited in tunnels.) In addition, operators of regional port facilities are anticipating more severe storm surge conditions than found in the historical record, and associated MPO planning efforts can build on these new planning assumptions.

The MPO agrees that if climate trends continue as projected, the conditions in the Boston region likely would include a rise in sea level coupled with storm-induced flooding, and more days with extreme temperatures that would affect the region’s infrastructure, economy, human health, and natural resources. While municipalities, MassDOT, and the MBTA oversee the design process for transportation infrastructure improvements in the region, the MPO has integrated resiliency into its scoring criteria used to evaluate projects for the LRTP and TIP.

The MPO developed an all-hazards planning application that shows the region’s transportation network in relation to natural hazard zones. This tool is used in conjunction with the MPO’s database of LRTP and TIP projects to determine if proposed projects are located in areas prone to flooding or at risk of seawater inundation from hurricane storm surges, or, in the long term, sea level rise. Transportation facilities in such hazard zones might benefit from flood protection measures, such as enhanced drainage systems, or adaptations for sea level rise.

Other actions that could be undertaken by the MPO and other transportation agencies to incorporate adaptation into the planning process include the following:

Through Executive Order 569, the Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs is required to work with the Secretary of Transportation and others to publish a statewide adaptation strategy. Both MassDOT and the MBTA are developing policies to implement this executive order. These agencies will identify the vulnerabilities within their systems and then identify resiliency measures to reduce their vulnerabilities. These actions will include embedding resiliency into all project development. The MPO can use this information when evaluating projects for funding in its LRTP and TIP.

The CA/T Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment was completed in 2015 and created the Boston Harbor Flood Risk Model. This model is being expanded to cover the entire Massachusetts coast and will be renamed the Massachusetts Coastal Flood Risk model. This model will be used to evaluate impacts associated with the current year, 2030, 2050, and 2070/2100 climate scenarios.18

In addition, MassDOT and the coordinating agencies are exploring ways to make climate data more accessible to municipalities.

The Commonwealth established a Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) grant program to support cities and towns as they identify climate change vulnerabilities, prioritize critical actions, and build community resiliency. The MVP Program provides funding and technical support to complete a community-led planning process that

When municipalities complete the planning process they become eligible for follow-on funding opportunities, including MVP action grants, and advanced standing in other grant opportunities.19

As of October 2018, designated communities in the MVP Program were Boston, Cambridge, Salem, Somerville, and Swampscott. Designated communities receive advanced standing in Massachusetts Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs grant programs. Participating communities include Acton, Arlington, Cohasset, Essex, Everett, Gloucester, Littleton, Manchester-by-the-Sea, Marblehead, Medford, Melrose, Milford, Natick, North Reading, Rockport, Norwood, Peabody, Sherborn, Stow, Weymouth, Winthrop, and Wrentham.

During fall 2017 and winter 2018, MPO staff collected feedback on transportation issues, needs, and opportunities for action from municipal planners and officials, transportation advocates, members of the public, and other stakeholders. During this outreach process, 78 respondents commented on maintenance and resiliency of the transportation system. This section summarizes comments by theme.

Respondents felt that it was important to maintain significant portions of the transportation network that are currently in disrepair. This interest was highlighted by state and municipal officials, transportation advocates, and residents. Maintenance concerns focused on the need to invest in the maintenance of MBTA infrastructure and the repair of roadway and pedestrian facilities.

Respondents felt that it was important to create a resilient transportation network that can evolve to mitigate the impacts of climate change, population growth, and inequality on the region. This interest was highlighted by state and municipal officials, transportation advocates, transit providers, and residents. Resiliency concerns centered around the need to plan for the impacts of climate change, particularly on public transit and in vulnerable communities, by promoting transit as an alternative to single-occupancy vehicles (SOVs) and by preparing facilities for extreme weather events.

Respondents also offered proposed solutions that focused on improvements to public transit, pedestrian and bicycling infrastructure, and roadway and bridge maintenance. These ideas are summarized below.

Since the MPO last updated its Needs Assessment in 2014, there have been several planning and policy changes that affect the content of this chapter:

MPO staff updated this chapter, based on these planning and policy changes, data availability, and other factors:

1 MassDOT’s Transit Asset Management Plan is scheduled to be finalized in July 2019.

2 Massachusetts Department of Transportation. 2017 Massachusetts Road Inventory Year End Report. March 2018. pg 58. Lane mile values exclude shoulders and auxiliary lanes.

3 MassDOT continues to measure pavement quality and to set statewide short-term and long-term targets in the MassDOT Performance Management Tracker using the Pavement Serviceability Index (PSI), which is a different index than IRI.

4 The MPO’s TIP evaluation criteria considers pavement to be in good condition if its IRI rating is less than 190, in fair condition if its IRI rating is between 191 and 320, and in poor condition if its IRI rating is greater than 320.

5 Local roads are not monitored under MassDOT’s Pavement Management Program.

6 FHWA’s IRI thresholds for good, fair, and poor condition differ from those currently used by the MPO. For federally required NHS pavement condition performance measures, IRI values considered good are those less than 95; those considered fair are between 95 and 170; and those considered poor are greater than 170.

7 Federal Highway Administration. “Tables of Frequently Requested NBI Information.” Bridges and Structures. Accessed May 27, 2019 at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/bridge/britab.cfm.

8 These 2018 values are based on bridge inventory data provided by MassDOT on December 31, 2018. Multiple bridge structures may serve a particular crossing.

9 National Bridge Inventory data is used to rate these components on a scale of zero (worst) to nine (best). The FHWA has classified these bridge ratings into good (seven, eight, or nine on the scale), fair (five or six), or poor (four or less).

10 Culverts are assigned an overall condition rating.

11 Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Massachusetts Pedestrian Transportation Plan. May 2019. Accessed May 27, 2019 at https://massdot.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=96339eb442f94ac7a5a7396a337e60c0.

12 Metropolitan Area Planning Council. “Local Access Score by MAPC.” Accessed May 27, 2019 at http://localaccess.mapc.org

13 Capital District Transportation Committee. CDTC Regional Sidewalk Inventory. Accessed May 27, 2019 at http://www.cdtcmpo.org/images/bike_ped/CDTC_Regional_Sidewalk_Inventory_Report.pdf.

14 Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Annual Report of the Performance and Asset Management Advisory Council. December 2018. Accessed May 27, 2019 at https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/06/25/2017%20Annual%20PAMAC%20Report.pdf, pg6.

15 Annual Report of the Performance and Asset Management Advisory Council, pg. 14. See also: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. MBTA Transit Asset Management Plan. Accessed May 27, 2019 at

https://www.ctps.org/data/calendar/pdfs/2019/MPO_0321_MBTA_TAM_Plan_2018.pdf

16 CATA adopted useful life criteria as defined in FTA Circular 5010.1E (Award Management Requirements). MWRTA adopted useful life criteria as defined in MassDOT’s Fully Accessible Vehicle Guide and in FTA Circular 5010.1E.

17 https://cdn.mbta.com/sites/default/files/fmcb-meeting-docs/reports-policies/2017-mbta-strategic-plan.pdf, page 23.

18 Massachusetts Department of Transportation. “Central Artery and Tunnel Pilot Project.” Climate Change Resiliency. Accessed May 27, 2019 at https://www.mass.gov/info-details/climate-change-resiliency#central-artery-and-tunnel-pilot-project-.

19 Commonwealth of Massachusetts. “Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness.” Resilient MA. Accessed May 27, 2019 at http://resilientma.org/mvp#resources.

< Chapter 4 - Safety Needs | Chapter 6 - Capacity Management and Mobility Needs >